Abstract

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a flexible polymer known for its multifaceted use in the medical and chemical fields. The most common use of PEG is through the process of PEGylation, which covalently attaches PEG to other molecules, such as proteins, to improve properties compared to the natural molecule. This review focuses on the pharmaceutical applications of PEG and examines the overall effects of PEGylation on protein stability, including the various types of stability affected (e.g., thermal, thermodynamic, kinetic, and proteolytic). Site-specific PEGylation is crucial for optimal pharmacological function and is discussed in detail. Furthermore, advancements in PEGylation beyond proteins, such as liposomes, nanoparticles, and oligonucleotides, are highlighted, paving the way for future research and applications. In conclusion, the increasing utility of PEGylation in pharmaceuticals underscores its significant impact and versatility.

Introduction

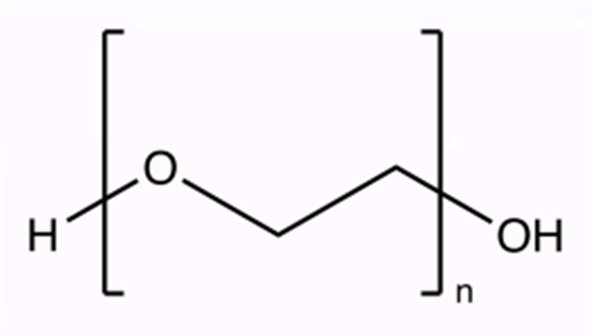

Polyethylene glycol (PEG; chemical formula: C2nH4n+2On+1) is a hydrophilic polymer widely used in various fields, including biology, chemistry, and medicine. PEG is known for being versatile, easy to manipulate, and biocompatible with minimal immunological reactions. Compared with other polymers, PEG is highly flexible and easy to control, yielding PEG polymers with a variety of molecular weights1’2’3. Further, PEG is colorless, odorless, non-toxic, and non-volatile. It is also unable to react with other substances readily under normal conditions, making it inert.

In a general sense, PEGylation is useful because it confers stealth properties to its host molecule. In other words, the molecule that PEG is attached to can bypass recognition by the body’s immune system, largely due to the properties of PEG4’25. Further, PEGylation increases the half-life of the nanocarrier, which means that the amount of time the drug stays in the body increases. Drugs with longer half-lives will remain effective for longer6’7. Also, by attaching PEG to molecules, the size of the drug compound increases, which makes it less likely to be filtered out in the urine. This directly reduces the required dosage frequency and further improves targeted drug delivery8. The effectiveness of PEG also depends on its structure, with branched PEG having better resistance than linear PEG2’9.

The purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive summary of existing articles and scientific research utilizing PEG and PEGylation. Specifically, this review will highlight recent advancements and effects of PEGylation on different types of molecules, which could potentially help improve clinical outcomes.

Methodology

A broad search was conducted across scientific journals like ResearchGate, PubMed, and Scopus. To filter by keywords and credible journals, Google Scholar was used. Keywords like ‘PEGylation,’ ‘protein stability,’ ‘thermal stability,’ ‘thermodynamic stability,’ ‘kinetic stability,’ ‘proteolytic stability,’ ‘nanoparticle PEGylation,’ ‘liposome PEGylation,’ ‘nucleic acid PEGylation,’ ‘anti-PEG antibodies,’ and ‘PEGylation challenges’ were utilized. All studies and articles used were from within the last 20 years, ranging from the year 2000 to 2025. The inclusion criteria were reviews that were peer-reviewed, published with substantial and thorough research, and primarily in English. Articles that were not relevant to the use of PEG in pharmaceutical environments were not included.

Discussion

History of PEG

Initially obtained from petroleum in 1859 by a Portuguese chemist named A.V. Lourenço, PEG was most widely known for its effects as a laxative to treat constipation2. However, its properties of hydrophilicity (i.e., water-loving), inertness, and biocompatibility make it useful in many applications. For example, PEG is used as a coating for drugs and implants to reduce immunologic reaction in the body2. Outside of the pharmaceutical industry, it has applications in the cosmetic and food industries10. For example, it is used to make skin conditioners, surfactants, emulsifiers, and cleansing agents 2. In the food industry, it is used as food packaging, delivery systems, and food coatings. Finally, it has been utilized to preserve the colors of the terracotta army discovered in China11.

Frank F. Davis, an American biochemist, contributed to a breakthrough in the 1970s when he first demonstrated PEGylation. This discovery was motivated by his desire to diminish immune responses against non-human proteins, which would therefore increase the activity of any drug inside the body. Davis first displayed PEGylation by attaching PEG to proteins like catalase and bovine serum albumin (BSA). He found that using PEG activated by cyanuric chloride increased the circulation time of proteins in blood and decreased immunogenicity2. This success led to the commercialization of PEGylation, with Davis co-founding Enzon Pharmaceuticals along with Abraham Abuchowski to develop PEGylated products. A PEGylated form of Adenosine deaminase, Adagen, was developed as one of the earliest forms of PEGylated medication. This and 15 other PEGylated medications have since been approved by the FDA for various diseases and therapies2.

| PEGylated Product | Uses |

| Adagen (approved early 1990s) | Treatment of “bubble boy disease” – a severe form of combined immunodeficiency illness |

| PEGaspargase (approved early 1990s) | Leukemia treatment |

| PEGademase (approved early 1990s) | Treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency disorder |

| Neulasta (approved early 1990s) | Increases white blood cell count after chemotherapy for cancer |

| Mircera (approved early 1990s) | Treatment of anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease |

| general PEGylated medications | More recently, undergoing clinical trials to treat wound healing, acromegaly, rheumatoid arthritis, neutropenia, hepatitis C, etc. |

| General PEGylated liposomes | Enhanced permeability and retention (EPR), used in cancer therapy |

| PEGylated proteins, peptides, and non-peptide molecules | Increased activity, increased plasma half-lives, reduced antigenicity, reduced antibody production |

| PEGylated therapeutic proteins | Used to protect the body’s digestive proteolytic enzymes |

| PEGylated asparaginase (with branching PEG) | withstands trypsin degradation (helps to increase half-life, reduced dosage frequency, etc.) |

| PEGylated nanocarriers | Improves the ability to target specific tumors |

Challenges in Commercial Scale-Up and Quality Control of PEGylation

The scientific and biomedical benefits of PEGylation for improving drug properties are immense and fairly well appreciated; however, these advances present an entirely different array of problems when transferring them from the laboratory to industrial-scale production. A complete understanding of PEGylation requires that one examine some of the fundamental issues other than its biochemical benefits that concern process scale-up, stringent quality control, and uniformity of the eventual PEGylated product12’13. In particular, these refer to optimizing reaction parameters for manufacturing purposes, reducing heterogeneity in the product, and building and validating analytical procedures to assure uniformity between batches concerning molecular weight, structure, and biological activity14’15’16’17. There are certainly other issues in the industry that must be overcome if PEGylated drugs are to be clinically translated, let alone widely.

PEGylation: Methods, Advantages, and Disadvantages

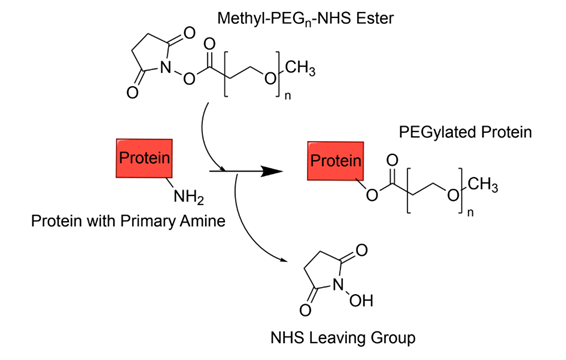

PEGylation refers to the covalent conjugation of PEG molecules to other molecules, such as proteins. PEGylation has been a huge advancement in many fields because it has improved the pharmacokinetics (the study of how drugs move through the body) and pharmacodynamics (chemical and physiological effects of drugs on the body) of protein therapeutics182’19. One of the primary purposes of PEGylation is to increase the apparent size and hydrophilicity of the protein, decreasing kidney filtration rates while increasing the aqueous solubility of proteins and the circulation time in the body20. Further, PEGylation has been shown to reduce immunogenicity and stabilize proteins. One main factor that improves the stability of proteins is protein hydration. Protein hydration refers to water molecules that form a network around the surface of a protein through hydrogen bonds21. PEG improves protein hydration by stabilizing water molecules around the protein and creating a larger hydrophilic region surrounding the protein called a hydration shell. This allows the protein to maintain its structure, reduce aggregation, and be more soluble22’23’24. Thus, PEGylation can yield pharmaceuticals with more optimal conditions, including effective drug delivery and efficacy20’2. With site-specific PEGylation, the site of attachment is crucial to maintain the efficacy of the protein therapeutic.Various methods have been utilized to achieve this, with several of the main methods discussed below.

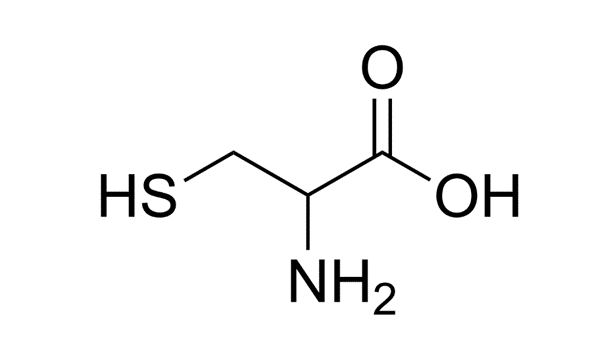

Thiol-selective PEGylation

Thiol-selective PEGylation is the attachment of PEG to a thiol group, which consists of a sulfur and hydrogen atom bound together. These thiol groups are found at the side chains of cysteine residues25. Cysteine is a particularly popular amino acid to target, largely due to its low frequency of about 2.2% or less, structural shielding, and reactive thiol group26’20. This means that cysteines make up a low percentage of proteins, and are scarcely found in proteins, which makes it an easier target for PEG to be attached without altering the function of the protein therapeutic. Furthermore, there are fewer reactive sites of cysteines, which makes it ideal for site-specific PEGylation. Unlike other PEGylation sites, the attachment of PEG at the thiol group is advantageous because it avoids unwanted reactions due to its high selectivity and does not disrupt the overall function of the protein, thereby maintaining the PEGylation’s targeted and specific nature25.

N-Terminus PEGylation

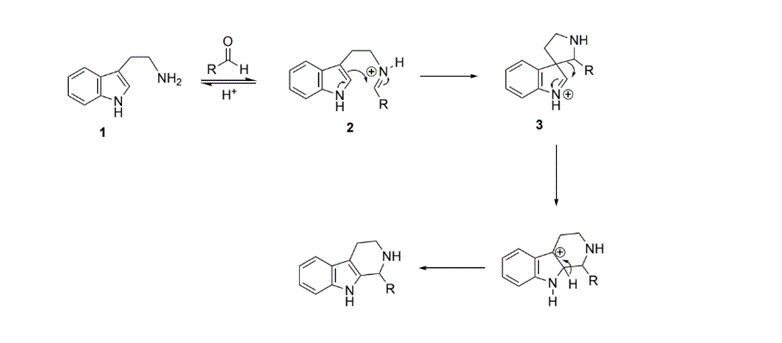

Additional amino acids that can be utilized for PEGylated include serine, threonine, and tryptophan. The middle or the N- N-terminus (the start of a protein with the free amine group) of serine and threonine can be oxidized, meaning they can be combined with oxygen and in the process, lose a hydrogen that allows new linkages to form27. As for tryptophan, the Pictet-Spengler reaction modifies the tryptophan residues in proteins by oxidizing the amino group on tryptophan, which creates stable bonds28.

| PEGylation method | Strengths | Limitations |

| Thiol-selective PEGylation | Targeted PEGylation due to the low frequency of cysteines20 Does not alter the function of the protein20 | The thiol groups are only present on cysteine residues, which might not be found in all proteins 20 |

| N- Terminus | Able to target a wider range of sites: tryptophan, threonine, or serine28. Still selective due to the limited N- N-terminus28. | Oxidation reactions might alter protein structure28. May be less predictable due to the targeting of non-cysteine residues28. |

However, PEGylation also has key disadvantages. In a review by Patel et. al, it was discussed that after a long period of time, PEGylated drugs accumulate in the macrophage system, which may have harmful effects. The macrophage system, which includes the kidneys and spleen, is very important due to its function of immune defense and clearing substances that are foreign to the body29.

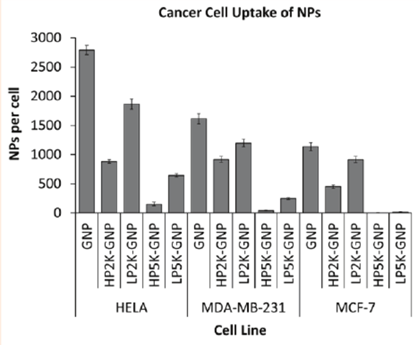

Accumulation in the macrophage system may lead to toxicity, as too much of a substance in the body can hinder and interfere with the normal functions of that part30. Another disadvantage is that the cellular uptake of PEGylated proteins can be affected. The hydrophilic PEG layer on the surface of a drug can hinder its ability to bind to its receptor (steric hindrance), making it a physical barrier and making the protein ineffective, depending on its intended use. It can also affect the way the protein is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, or excreted29. For example, in a study done by Cruje and Chithrani, the effect of PEGylation using different lengths (2 kDa and 5 kDa) and densities (1 PEG/nm² and 1 PEG/2 nm²) was observed in terms of cellular uptake. In the study, three different cancer cell lines, both hormone-sensitive and resistant, were used: HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-7. PEG chains of different lengths and densities were conjugated with gold nanoparticles called GNPs (diameter 50 nm), and the uptake of these complexes by the three cancer cells was observed31. As seen from the figure below, the GNP with no PEG attached had the greatest cellular uptake of nanoparticles in all three cell lines. In HELA cells, the NP uptake was observed to be 2800 NPs/cell, in MDA-MB-231 cells it was about 1600 NPs/cell, and in MCF-7 it was observed to be around 1100 NPs/cell.

Some additional concerns in the usage of PEG recently have also been discovered, like immunogenicity concerns, specifically anti-PEG antibody production, and the Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) phenomenon. Usually, when PEG is administered into the body regularly, the body has no problem ingesting it, but when PEG is administered for the first time, the body may recognize it as a foreign substance and begin to produce anti-PEG antibodies to secrete PEG out of the system. This, in turn, could directly lead to the ABC phenomenon, which is when excess PEGylated drugs accumulate in the macrophage system and have to be cleared rapidly by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). This could limit the efficacy of the drug due to the target tissues not receiving enough of the drug32.

Recent chemical advancements have made PEGylation even more reliable, as they ensure PEG’s ability to modify proteins while maintaining the original protein structure and function. Some strategies that have been developed to mitigate these challenges include De-PEGylation and the enhancement of cellular uptake (active targeting). De-PEGylation is a strategy that helps fight PEG’s property of steric hindrance. It uses PEG conjugates (cleavable PEG lipids) that can be removed once the protein reaches its target site33. Some cleavable bonds that are used in De- PEGylation include pH- sensitive bonds that break down in acidic conditions (such as those of endosomes or tumor environments), enzyme- sensitive bonds that are broken in the presence of specific enzymes, or redox- sensitive bonds like disulfide bonds that are sensitive to reductive environments34. A limitation that may occur when using this method could be incomplete cleavage. In the case that an incomplete cleavage occurs, not all the PEG chains around the drug break off, making the remaining PEG chains still cause steric hindrance, reducing the cellular uptake of the PEGylated drug35. Active targeting is another method to enhance cellular uptake for PEGylated drugs. Molecules that bind to specific receptors, or ligands, are attached to the surface of PEGylated carriers. This allows for cells to effectively bind to their target molecules and overcome PEG’s steric hindrance properties36. However, the main limitation of using this method is intracellular trapping and degradation. After the drug binds to the target, it can sometimes get trapped inside cellular compartments like lysosomes (organelles that break down cellular waste) and get broken down and excreted from the system. This would stop it from reaching its target cell and fulfill its function37’38.

Protein Stability Following PEGylation

PEG can have many different effects on different proteins. In this section, we will discuss specific aspects of protein stability that can be altered upon PEGylation.

Thermal

Thermal stability of a protein refers to its ability to retain structure in the presence of higher temperatures. Some key factors influencing thermal stability include protein structure, hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions, and hydrophobic interactions. A study by Treetharnmathurot et. al was done to understand how the different factors of PEG affected the thermal stability of trypsin, including the molecular weight of PEG and the chemistry used for PEGylation39. This study utilized different molecular weights of monomethoxy polyethylene glycol (mPEG) and various chemicals in different linking chemistries, including succinic anhydride, cyanuric chloride, and tosyl chloride. In order to test the thermal stability, buffers between 30 and 70 degrees were prepared in which native trypsin and PEGylated conjugates were incubated39. The activity of the trypsin was then measured by how they reacted to Benzoyl Arginine-p-nitroanilide (BAPNA) and Nα-Benzoyl-L-arginine ethyl ester (BAEE), which are synthetic substrates used to measure the enzymatic activities of trypsin40. As a result, it was seen that PEGylation can, in fact, increase thermal stability, but for most activity of the protein, mPEG with a molecular weight of 5000 g/mol was the ideal molecular weight39. The results indicated that as temperature increases in increments of 10 ℃, starting from 30 ℃, the % residual activity (activity of the complex compared to its original activity level) of the trypsin mPEG complex decreases, with about 35% residual activity of the trypsin alone and about 60% residual activity of the trypsin and 5000 g/mol mPEG complex at 50 ℃ with the BAPNA substrate. Results showed a very similar trend for the BAEE substrate as well.

Thermodynamic

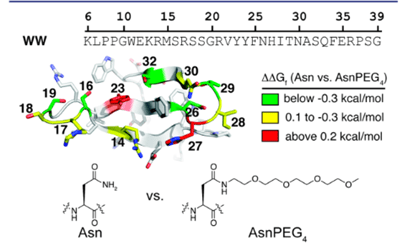

Thermodynamic stability is the capability of a protein to maintain its original structure under different environmental stressors41’42. A big indicator of this type of stability is the free energy difference between the original and the unfolded state, where a lower free energy suggests a more stable protein. Thermodynamic stability can be influenced by enthalpy and entropy, and environmental factors, such as changes in pH or temperature. Some more factors for assessing thermodynamic stability include protein dynamics and folding pathways. Protein dynamics refers to the movements and conformational changes proteins go through that are necessary for them to perform biological functions. Some examples of protein dynamics include enzyme catalysis, signal transduction, and folding into its correct 3D shape43’44’45. PEG influences protein dynamics by decreasing the molecular flexibility of proteins and restricting their movement so that these proteins have less freedom to alter their configuration, possibly into something less stable24. The criteria for selecting PEGylation sites on proteins to expand thermodynamic and proteolytic stability is discussed in a study done by Lawrence et. al. This study used the WW domain, a site on a protein that mediates protein- protein interactions (shown in figure 6), of the protein Pin1 as the model and as a result, it showed that certain PEGylation sites increased stability, whereas others had no effect or a destabilizing effect41

Another study conducted by Santos et. al. analyzed the stability of horse heart cytochrome c (cyt-c), a protein used for electron transfers and biosensing chemicals, following PEGylation. They used two forms of PEG-coated cyt- c, cyt- c PEGylated with 4 PEG chains (Cyt–c–PEG–4) and cyt- c PEGylated with 8 PEG chains (Cyt–c–PEG–8), and compared them with normal cyt-c to understand how long they can stay active47. Circular dichroism spectroscopy, a type of light spectroscopy used to study the shape and structure of proteins, was used in this study to look at the structural changes of PEGylated and non-PEGylated cyt-c48. Additionally, Arrhenius equations were used to determine the activation energy and other conditions. For thermodynamic stability, it was found that PEGylation increased the thermostability of cyt-c and increased its half-life during thermal inactivation. For example, at 70°C, the half-life of cyt-c was 4.00 h, whereas the half-life of the PEGylated cyt-c, Cyt–c–PEG–4 and Cyt–c–PEG–8 was 6.84 and 9.05, respectively. It was also found that the activation energy for the complex to denature was higher, as for the native Cyt-c it was 50.51±1.71 kJ mol⁻¹, Cyt-c-PEG-4 was 72.63±0.89 kJ mol–¹, and for Cyt-c-PEG-8: 63.36±1.66 kJ mol⁻¹, showing more resistance to unfolding47.

Kinetic

The kinetic stability of a protein refers to the free energy barrier between the native and denatured conformations of the protein. Kinetic stability is characterized by the folding versus unfolding rates of the proteins along with energy barriers, with a higher kinetic stability signifying a higher energy barrier and lower chance of denaturation49. The folding pathway of a protein refers to the process by which a protein folds from its unfolded structure to its native, original structure50. In the study used to investigate PEGylation’s effect on cyt- c, its kinetic stability is also discussed. The article highlights improvements in the kinetic stability through the improvement of the protein folding pathway. With the help of PEGylation, the tertiary structure (overall 3D structure) of cyt- c was made more stable, allowing it to maintain its catalytic activity at increased temperatures51. To come to these conclusions, some parameters were first determined, like the Michaelis constant (Km), maximum rate (Vmax), and turnover number (kcat), which help identify how fast the enzyme catalyzes reactions. The enzyme half-life was also calculated, which is a direct measure of kinetic stability because it shows how long the enzyme keeps its activity after being denatured52.

| Parameter | Native Cyt-c | Cyt-c-PEG-4 | Cyt-c-PEG-8 |

| Km(mM) | 0.23±0.01 | 0.23±0.01 | 0.24±0.01 |

| Vmax(µmol min⁻¹ mg⁻¹) | 124.64±0.02 | 122.95±0.06 | 123.63±0.08 |

| kcat(s⁻¹) | 1.64±0.01 | 1.61±0.01 | 1.62±0.01 |

Proteolytic

Proteolytic stability is the ability of a protein to not degrade in the presence of proteolytic enzymes. Proteolytic enzymes break down proteins into monomers, reducing the efficacy of the protein53. A study by Zhang et. al was conducted to modulate fibronectin with PEG to ultimately reduce its susceptibility to proteolysis and increase its ability to repair tissues in chronic wounds54. As a result, it was seen that Lysine-PEGylated FN showed more proteolytic stability and that it has a positive correlation with the molecular size of the PEG attached. The larger the mass/ weight, the slower the rate of proteolysis, or the breakdown of proteins into amino acids54. As seen in Figure 7 below, native FN degrades at a much faster pace than its PEGylated counterparts. As the molecular weight of the PEG chains increases (FN-PEG2, FN-PEG5, FN-PEG10), the rate at which the FN degrades slows down, with the highest amount of intact FN likely being with FN-PEG1054.

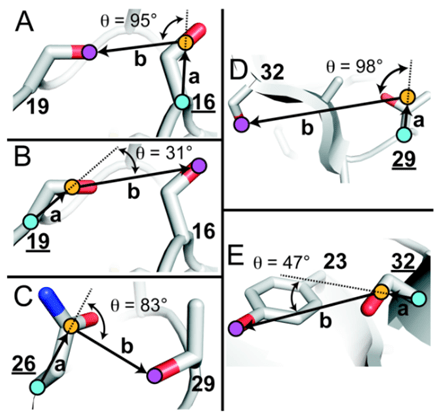

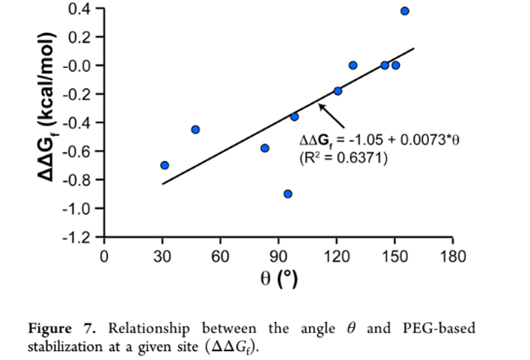

PEGylation was also shown to reduce protein flexibility, which in turn makes a stronger protein core, increasing protein stability. In another study, the influence on the protein srSH3 due to PEGylation was evaluated. The findings show that attaching PEG increased srSH3’s thermodynamic stability and reduced the protein unfolding rate, strengthening its overall stability46. Some other studies show negative effects of PEG on the stability of the protein itself, as shown in the study by Santos et al. done on cyt-C and BSA (Santos et al., 2019). In this study, although the thermodynamic stability of the protein was enhanced through the resistance of the protein to denature, the protein’s catalytic performance decreased, evident in its reduced maximum reaction rate (vmax) and substrate affinity measured by the Michaelis constant (Km). To better explain the variability, a review by Lawrence et al. drew some conclusions about the criteria for PEGylation to have the desired effects on protein stability46. One of the criteria identified was the orientation of side chains near PEGylation sites. It was observed that as the angle between alpha carbons (carbon atoms bound to functional groups), the side chain center of masses of the protein’s side chain at the specific PEGylation site, and OH containing side chains increases, the change in folding free energy (ΔΔGf ) increased linearly as shown in figure 8 below. ΔΔGf is used to measure the stability of the protein, as a positive ΔΔGf indicates increased stability and a negative ΔΔGf indicates decreased stability41. Therefore, although the specific differences in these criteria were not mentioned in the previous studies done by Santos et. al, Zhang et. al, and Liu et. al, the difference in results of the proteolytic stabilities can likely be attributed to these characteristics.

of mass (COM), and oxygens of the nearest OH-containing side chain are highlighted with blue-, orange-, and purple-filled circles, respectively. (Adapted from Lawrence et al., 2014)

PEGylation on Protein Aggregation

Protein aggregation refers to the clumping of proteins, leading to a loss of protein function. Protein aggregation is largely attributed to protein misfolding and has been associated with several neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or Huntington’s disease55’42. In order to see the effects of PEGylation on protein aggregation in pharmaceuticals and the effectiveness in medications, an insightful study was conducted by Rajan et al, investigating the aggregation and precipitation of GCSF following PEGylation. This study utilized granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF), a protein that has a tendency to aggregate and precipitate (become insoluble), and attached different lengths of PEG to its N- N-terminus42. The modified GCSF was now called 20 kDa PEG-GCSF and 5 kDa PEG-GCSF. These proteins, along with GCSF on its own, were incubated in a fluid that had similar conditions like pH (6.9) and temperature (37°C) of body fluid. The protein, with a concentration of 5 mg/mL, was placed in a 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer. Protein stability was measured using centrifugation, which involved spinning the sample at high speeds, and turbidity measurements, where increased turbidity (e.g., cloudiness) indicates more precipitation and decreased protein stability (Rajan et al., 2006). As seen in Figure 6, the PEGylated GCSF was more soluble. Although it was found that both the PEGylated and non-PEGylated GCSF aggregated, the PEGylated GCSF formed soluble aggregates, which are much more useful in medications as they can actually circulate through the body without being filtered out42.

PEGylation of Additional Molecules

While the focus of this review has been on discussing PEGylation of protein therapeutics, additional molecules can be PEGylated using similar chemistries, improving their therapeutic properties compared to non-PEGylated structures. In this section, we will discuss a few molecules and therapeutics that can be PEGylated.

Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles are particles with diameters between 1 and 100 nanometers, with more organic nanoparticles being up to 300 nanometers that come in many different types of structures (Nanoparticle Size – an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, n.d.). PEGylation is useful in developing nanoparticles that have targeted applications in healthcare, as demonstrated in a study done by Cheng et. al.56. This study mainly focuses on developing nanoparticles using Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-block-Poly(ethylene glycol)-carboxylic acid (PLGA-b-PEG-COOH). It also explores the effects of various parameters such as polymer concentration, solvent water miscibility, and water-to-solvent ratio on the nanoparticle size. To do this, Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-carboxylic acid (PLGA-COOH) was conjugated with Amino-Poly(ethylene glycol)-carboxylic acid (NH2-PEG-COOH) to make PLGA-b-PEG-COOH. As a result, it was seen that the solvent type and water miscibility influenced the nanoparticle size, where the more soluble the solvent was, the smaller the nanoparticle size. Increasing polymer concentrations showed a linear relationship with nanoparticle size, whereas solvent to water ratios did not show a huge effect on size, as long as the ratios remained in the range of 0.1 to 0.556.

Liposomes

Liposomes are spherical nanoparticles composed of lipid bilayers and an aqueous core57’58. A study done by Naakamura et. al focuses on targeting liposomes to increase the effectiveness of drug delivery systems59. They found that PEGylation of liposomes can increase their blood circulation time by reducing their uptake by phagocytic cells in the liver and spleen. However, the method used to modify liposomes with PEG showed degradation and reduced capability for the PEGylated liposomes to work59. The study then proposed the post-modification method, which aims to maintain the stability of the liposomes by only modifying the outer surface of the liposome. To put this to the test, male Sprague Dawley rats were injected with liposomes containing two different types of chemotherapy drugs- Doxorubicin (DXR) and Vincristine (VCR), both post-modified and pre-modified59. Their blood was collected at different time intervals after the administration, and then high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to determine the drug concentration in the plasma. As a result, the post-modification method was found to be much more beneficial59. It was seen that the liposomes that used the post-modification method had enhanced blood circulation that those with the pre-modification method59.

Nucleic Acids

Nucleic acids are biomolecules that store and express genomic information. Some commonly known types of nucleic acids are deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA)60. A study done by Üzgün et. al attempted to explore whether or not PEGylation increases the delivery of nucleic acids in the body. The main objective of the study was to compare how PEGylated vs. non-PEGylated polymer carriers performed with messenger RNA (mRNA) and plasmid DNA (pDNA)61. mRNA is a type of nucleic acid that is the translated version of the DNA that helps proteins and amino acids assemble62. pDNA, on the other hand, is a circular, double-stranded DNA that exists and replicates independently of the main chromosomal DNA. They are useful because scientists can use them to transfer genes into new cells63. Specifically, the two types of polymers used in the study were linear polyethylenimine (l-PEI), which binds well with mRNA, and poly-N, N-dimethylaminoethylmethacrylate (PDMAEMA), which binds well with DNA. These two polymers were PEGylated and an agarose gel retardation assay was run for both of them to see which one would bind more effectively after being PEGylated. It was found that PEGylation improved the binding and transfection of mRNA, while it had the opposite effect on pDNA, where it actually reduced the binding64.

Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides are short pieces of DNA monomers, or nucleotides. Typically, oligonucleotides consist of 13-25 nucleotides, making them the shortest polymers of nucleic acids65. A review by Shokrzadeh et. al explains the outcomes of using short PEG chains to modify antisense oligonucleotides. Antisense oligonucleotides are fundamentally single-stranded DNA or RNA that are made to bind to complementary RNA sequences. This study states that utilizing short PEG chains, specifically PEG12 chains, which contain twelve ethylene glycol units, instead of long PEG chains (molecular weight above 20kDa) maintains the structural integrity of the oligonucleotide66. In another study by Wang et. al, the same PEGylation of oligonucleotides is discussed. Specifically, the authors discuss the development of DNA bottlebrush structures through the use of PEGylation67. The DNA bottlebrush structure consists of a DNA backbone with about 25-35 PEG side chains attached to it, along with parts that target specific genes. To develop these DNA bottlebrush structures, a technique called hybridization chain reaction was used. The study observed that these bottlebrush structures were not taken up very well by the cells, but they were highly effective in stopping the growth of lung cancer cells with the KRAS mutation without causing any further toxicity, making them safe for the body67.

Conclusions and Limitations

PEG and PEGylation have advanced the pharmaceutical and biochemical fields, improving qualities such as biocompatibility, immunogenicity, and hydrophilicity68’7. PEGylation is commonly utilized in protein conjugation, but it is quite useful with other molecules and therapeutics as well, including nanoparticles and oligonucleotides (30). However, it is also important to note that PEG does not always have a uniformly positive effect on stability. There are some trade-offs between the benefits, such as improved pharmacokinetics, and the drawbacks, such as the reduced bioactivity of PEG. PEGylation offers several advantages to therapeutics, including extended circulation times, increased target efficiency, reduced immunogenicity, and enhanced solubility2. However, despite these advantages, PEGylation does have some negative consequences, like the risk of reduced cellular uptake due to the steric hindrance caused by the hydrophilic PEG coating and the accumulation in tissues, both of which can be harmful in their ways 2. New ways to combat these risks have also been developed, such as de-PEGylation and active targeting, which minimize the downsides of using PEG. Some studies show no beneficial or destabilizing effects, which may be due to the PEG conjugation strategy, differences in PEG chain lengths, and PEG and protein orientations.

| Factors Determining the Enhanced Function of PEG | Factors Determining the Compromised Function of PEG |

| Extended half-life and reduced clearance from the body 2. | Accumulation in tissues causes toxicity in the body 2 |

| Improved Stability- reduced denaturation and aggregation, maintaining folding structures69 | Immunogenicity to PEG- creation of “PEG antibodies” leading to Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) 2 |

| Reducing the tendency for the body to produce an immune response – Decreased Immunogenicity2 | Reduced Cellular Uptake 2 |

Due to the quickly evolving field of medicine, technology, and biochemistry, these issues are being addressed, and research is continuously happening to minimize side effects or harm to the body.

References

- Jang, H.-J., Shin, C. Y., & Kim, K.-B. (2015). Safety Evaluation of Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Compounds for Cosmetic Use. Toxicological Research, 31(2), 105–136. https://doi.org/10.5487/TR.2015.31.2.105 [↩]

- (PDF) An Overview of PEGylation’s History, Benefits, and Methods for Resolving the PEG Dilemma. (n.d.). ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.35629/7781-080611161124 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Description, History, & Uses | Britannica. (2025, April 21 https://www.britannica.com/science/polyethylene-glycol [↩]

- Lu, X., & Zhang, K. (2018). PEGylation of therapeutic oligonucletides: From linear to highly branched PEG architectures. Nano Research, 11(10), 5519–5534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-018-2131-8 [↩]

- (PDF) Polyethylene Glycol Density and Length Affects Nanoparticle Uptake by Cancer Cells. (n.d.). ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.15406/jnmr.2014.01.00006 [↩]

- Lu, X., & Zhang, K. (2018). PEGylation of therapeutic oligonucletides: From linear to highly branched PEG architectures. Nano Research, 11(10), 5519–5534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-018-2131-8; (PDF) An Overview of PEGylation’s History, Benefits, and Methods for Resolving the PEG Dilemma. (n.d.). ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.35629/7781-080611161124 [↩]

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Description, History, & Uses | Britannica. (2025, April 21). https://www.britannica.com/science/polyethylene-glycol [↩] [↩]

- PDF) An Overview of PEGylation’s History, Benefits, and Methods for Resolving the PEG Dilemma. (n.d.). ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.35629/7781-080611161124 [↩]

- Li, W., Zhan, P., De Clercq, E., Lou, H., & Liu, X. (2013). Current drug research on PEGylation with small molecular agents. Progress in Polymer Science, 38(3), 421–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2012.07.006 [↩]

- Ibrahim, M., Ramadan, E., Elsadek, N. E., Emam, S. E., Shimizu, T., Ando, H., Ishima, Y., Elgarhy, O. H., Sarhan, H. A., Hussein, A. K., & Ishida, T. (2022). Polyethylene glycol (PEG): The nature, immunogenicity, and role in the hypersensitivity of PEGylated products. Journal of Controlled Release, 351, 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.09.031 [↩]

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Description, History, & Uses | Britannica. (2025, April 21). https://www.britannica.com/science/polyethylene-glycol [↩]

- Bento, C., Katz, M., Santos, M. M. M., & Afonso, C. A. M. (2024). Striving for Uniformity: A Review on Advances and Challenges To Achieve Uniform Polyethylene Glycol. Organic Process Research & Development, 28(4), 860–890. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.3c00428 [↩]

- Timothy Riley, P., & Riggs-Sauthier, J. (2008). The Benefits and Challenges of PEGylating Small Molecules. 32. https://www.pharmtech.com/view/benefits-and-challenges-pegylating-small-molecules [↩]

- Ciszewski, P. (2025, January 25). Optimizing Therapeutic Proteins Through PEGylation: Key Parameters and Impacts. CheckRare. https://checkrare.com/optimizing-therapeutic-proteins-through-pegylation/ [↩]

- Santhanakrishnan, K. R., Koilpillai, J., & Narayanasamy, D. (n.d.). PEGylation in Pharmaceutical Development: Current Status and Emerging Trends in Macromolecular and Immunotherapeutic Drugs. Cureus, 16(8), e66669. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.66669 [↩]

- Simberg, D., Barenholz, Y., Roffler, S. R., Landfester, K., Kabanov, A. V., & Moghimi, S. M. (n.d.). PEGylation technology: Addressing concerns, moving forward. Drug Delivery, 32(1), 2494775. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2025.2494775 [↩]

- Wang, X.-D., Wei, N.-N., Wang, S.-C., Yuan, H.-L., Zhang, F.-Y., & Xiu, Z.-L. (2018). Kinetic Optimization and Scale-Up of Site-Specific Thiol-PEGylation of Loxenatide from Laboratory to Pilot Scale. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 57(44), 14915–14925. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.8b02613 [↩]

- Overview of Pharmacokinetics—Clinical Pharmacology. (n.d.). Merck Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/clinical-pharmacology/pharmacokinetics/overview-of-pharmacokinetics [↩]

- Pharmacodynamics—An overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/pharmacodynamics [↩]

- Pasut, G., & Veronese, F. M. (2012). State of the art in PEGylation: The great versatility achieved after forty years of research. Journal of Controlled Release, 161(2), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.10.037 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Nakagawa, H., & Tamada, T. (2021). Hydration and its Hydrogen Bonding State on a Protein Surface in the Crystalline State as Revealed by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Frontiers in Chemistry, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.738077 [↩]

- PEGylation of Proteins: A Structural Approach. (n.d.). Retrieved June 3, 2025, from https://www.biopharminternational.com/view/pegylation-proteins-structural-approach?utm_source= [↩]

- Supramolecular PEGylation of biopharmaceuticals | PNAS. (n.d.). Retrieved June 3, 2025, from https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1616639113?utm_source= [↩]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, J. A., Solá, R. J., Castillo, B., Cintrón-Colón, H. R., Rivera-Rivera, I., Barletta, G., & Griebenow, K. (2008). Stabilization of α-Chymotrypsin upon PEGylation Correlates with Reduced Structural Dynamics. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 101(6), 1142–1149. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.22014 [↩] [↩]

- Activated PEGs for Thiol PEGylation—JenKem. (n.d.). JenKem Technology USA. Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://jenkemusa.com/activated-pegs-thiol-pegylation [↩] [↩]

- Go, Y.-M., Chandler, J. D., & Jones, D. P. (2015). The Cysteine Proteome. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 84, 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.022 [↩]

- Oxidize. (2025, May 28). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/oxidize; Zuma, L. K., Gasa, N. L., Makhoba, X. H., & Pooe, O. J. (2022). Protein PEGylation: Navigating Recombinant Protein Stability, Aggregation, and Bioactivity. BioMed Research International, 2022(1), 8929715. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8929715 [↩]

- Zuma, L. K., Gasa, N. L., Makhoba, X. H., & Pooe, O. J. (2022). Protein PEGylation: Navigating Recombinant Protein Stability, Aggregation, and Bioactivity. BioMed Research International, 2022(1), 8929715. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8929715 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- (PDF) An Overview of PEGylation’s History, Benefits, and Methods for Resolving the PEG Dilemma. (n.d.) . ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.35629/7781-080611161124 [↩] [↩]

- Organ failure. (n.d.). Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24679-organ-failure [↩]

- (PDF) Polyethylene Glycol Density and Length Affects Nanoparticle Uptake by Cancer Cells. (n.d.). ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.15406/jnmr.2014.01.00006 [↩] [↩]

- (PDF) An Overview of PEGylation’s History, Benefits, and Methods for Resolving the PEG Dilemma. (n.d.) ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.35629/7781-080611161124 [↩]

- Hatakeyama, H., Akita, H., & Harashima, H. (2013). The Polyethyleneglycol Dilemma: Advantage and Disadvantage of PEGylation of Liposomes for Systemic Genes and Nucleic Acids Delivery to Tumors. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 36(6), 892–899. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.b13-00059 [↩]

- Makharadze, D., del Valle, L. J., Katsarava, R., & Puiggalí, J. (2025). The Art of PEGylation: From Simple Polymer to Sophisticated Drug Delivery System. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073102 [↩]

- Govan, J. M., McIver, A. L., & Deiters, A. (2011). Stabilization and Photochemical Regulation of Antisense Agents through PEGylation. Bioconjugate Chemistry, 22(10), 2136–2142. https://doi.org/10.1021/bc200411n [↩]

- Ciftci, F., Özarslan, A. C., Kantarci, İ. C., Yelkenci, A., Tavukcuoglu, O., & Ghorbanpour, M. (2025). Advances in Drug Targeting, Drug Delivery, and Nanotechnology Applications: Therapeutic Significance in Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics, 17(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17010121 [↩]

- Cooper, G. M. (2000a). Lysosomes. In The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9953/ [↩]

- Li, J., Wang, Q., Xia, G., Adilijiang, N., Li, Y., Hou, Z., Fan, Z., & Li, J. (2023). Recent Advances in Targeted Drug Delivery Strategy for Enhancing Oncotherapy. Pharmaceutics, 15(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15092233 [↩]

- Treetharnmathurot, B., Ovartlarnporn, C., Wungsintaweekul, J., Duncan, R., & Wiwattanapatapee, R. (2008). Effect of PEG molecular weight and linking chemistry on the biological activity and thermal stability of PEGylated trypsin. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 357(1), 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.01.016 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Bapna | Sigma-Aldrich. (n.d.). Retrieved June 11, 2025, from https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/US/en/search/bapna?focus=products&page=1&perpage=30&sort=relevance&term=bapna&type=product [↩]

- Lawrence, P. B., Gavrilov, Y., Matthews, S. S., Langlois, M. I., Shental-Bechor, D., Greenblatt, H. M., Pandey, B. K., Smith, M. S., Paxman, R., Torgerson, C. D., Merrell, J. P., Ritz, C. C., Prigozhin, M. B., Levy, Y., & Price, J. L. (2014). Criteria for Selecting PEGylation Sites on Proteins for Higher Thermodynamic and Proteolytic Stability. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 136(50), 17547–17560. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja5095183 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Rajan, R. S., Li, T., Aras, M., Sloey, C., Sutherland, W., Arai, H., Briddell, R., Kinstler, O., Lueras, A. M. K., Zhang, Y., Yeghnazar, H., Treuheit, M., & Brems, D. N. (2006). Modulation of protein aggregation by polyethylene glycol conjugation: GCSF as a case study. Protein Science : A Publication of the Protein Society, 15(5), 1063–1075. https://doi.org/10.1110/ps.052004006 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Miller, M. D., & Phillips, G. N. (2021). Moving beyond static snapshots: Protein dynamics and the Protein Data Bank. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 296, 100749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100749 [↩]

- Nam, K., & Wolf-Watz, M. (2023). Protein dynamics: The future is bright and complicated! Structural Dynamics, 10(1), 014301. https://doi.org/10.1063/4.0000179 [↩]

- Protein Dynamics—An overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Retrieved June 3, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/protein-dynamics [↩]

- Lawrence, P. B., Gavrilov, Y., Matthews, S. S., Langlois, M. I., Shental-Bechor, D., Greenblatt, H. M., Pandey, B. K., Smith, M. S., Paxman, R., Torgerson, C. D., Merrell, J. P., Ritz, C. C., Prigozhin, M. B., Levy, Y., & Price, J. L. (2014). Criteria for Selecting PEGylation Sites on Proteins for Higher Thermodynamic and Proteolytic Stability. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 136(50), 17547–17560. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja5095183 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Santos, J. H. P. M., Carretero, G., Ventura, S. P. M., Converti, A., & Rangel-Yagui, C. O. (2019). PEGylation as an efficient tool to enhance cytochrome c thermostability: A kinetic and thermodynamic study. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 7(28), 4432–4439. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TB00590K [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Circular dichroism spectroscopy of membrane proteins—PubMed. (n.d.). Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27347568/ [↩]

- Anderson, D. M., Jayanthi, L. P., Gosavi, S., & Meiering, E. M. (2023). Engineering the kinetic stability of a β-trefoil protein by tuning its topological complexity. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 10, 1021733. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2023.1021733 [↩]

- Cooper, G. M. (2000b). Protein Folding and Processing. In The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9843/ [↩]

- Rehman, I., Kerndt, C. C., & Botelho, S. (2025). Biochemistry, Tertiary Protein Structure. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470269/; Santos, J. H. P. M., Carretero, G., Ventura, S. P. M., Converti, A., & Rangel-Yagui, C. O. (2019). PEGylation as an efficient tool to enhance cytochrome c thermostability: A kinetic and thermodynamic study. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 7(28), 4432–4439. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TB00590K [↩]

- Santos, J. H. P. M., Carretero, G., Ventura, S. P. M., Converti, A., & Rangel-Yagui, C. O. (2019). PEGylation as an efficient tool to enhance cytochrome c thermostability: A kinetic and thermodynamic study. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 7(28), 4432–4439. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TB00590K [↩]

- Report – Strategies for boosting proteolytic resistance in proteins – University of Gdańsk. (n.d.). Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://repozytorium.bg.ug.edu.pl/info/report/UOGc27f256dad6446e89e11e4c82a80ad94/ [↩]

- Zhang, C., Desai, R., Perez-Luna, V., & Karuri, N. (2014). PEGylation of lysine residues improves the proteolytic stability of fibronectin while retaining biological activity. Biotechnology Journal, 9(8), 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.201400115 [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Merlini, G., Bellotti, V., Andreola, A., Palladini, G., Obici, L., Casarini, S., & Perfetti, V. (2001). Protein aggregation. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 39(11), 1065–1075. https://doi.org/10.1515/CCLM.2001.172 [↩]

- Cheng, J., Teply, B. A., Sherifi, I., Sung, J., Luther, G., Gu, F. X., Levy-Nissenbaum, E., Radovic-Moreno, A. F., Langer, R., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2007). Formulation of functionalized PLGA–PEG nanoparticles for in vivo targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials, 28(5), 869–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.047 [↩] [↩]

- Liposome—An overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/liposome [↩]

- Nsairat, H., Khater, D., Sayed, U., Odeh, F., Bawab, A. A., & Alshaer, W. (2022). Liposomes: Structure, composition, types, and clinical applications. Heliyon, 8(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09394 [↩]

- Nakamura, K., Yamashita, K., Itoh, Y., Yoshino, K., Nozawa, S., & Kasukawa, H. (2012). Comparative studies of polyethylene glycol-modified liposomes prepared using different PEG-modification methods. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Biomembranes, 1818(11), 2801–2807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.06.019 [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Nucleic Acids. (n.d.). Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Nucleic-Acids [↩]

- Üzgün, S., Nica, G., Pfeifer, C., Bosinco, M., Michaelis, K., Lutz, J.-F., Schneider, M., Rosenecker, J., & Rudolph, C. (2011). PEGylation Improves Nanoparticle Formation and Transfection Efficiency of Messenger RNA. Pharmaceutical Research, 28(9), 2223–2232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-011-0464-z [↩]

- Messenger RNA (mRNA). (n.d.). Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Messenger-RNA-mRNA [↩]

- Plasmid DNA – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/plasmid-dna [↩]

- Üzgün, S., Nica, G., Pfeifer, C., Bosinco, M., Michaelis, K., Lutz, J.-F., Schneider, M., Rosenecker, J., & Rudolph, C. (2011). PEGylation Improves Nanoparticle Formation and Transfection Efficiency of Messenger RNA. Pharmaceutical Research, 28(9), 2223–2232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-011-0464-z [↩]

- Oligonucleotide—An overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Retrieved June 2, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/oligonucleotide [↩]

- Shokrzadeh, N., Winkler, A.-M., Dirin, M., & Winkler, J. (2014). Oligonucleotides conjugated with short chemically defined polyethylene glycol chains are efficient antisense agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 24(24), 5758–5761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.10.045 [↩]

- Wang, Y., Wang, D., Jia, F., Miller, A., Tan, X., Chen, P., Zhang, L., Lu, H., Fang, Y., Kang, X., Cai, J., Ren, M., & Zhang, K. (2020). Self-Assembled DNA–PEG Bottlebrushes Enhance Antisense Activity and Pharmacokinetics of Oligonucleotides. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 12(41), 45830–45837. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c13995 [↩] [↩]

- Jang, H.-J., Shin, C. Y., & Kim, K.-B. (2015). Safety Evaluation of Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Compounds for Cosmetic Use. Toxicological Research, 31(2), 105–136. https://doi.org/10.5487/TR.2015.31.2.105 [↩]

- Lawrence, P. B., Gavrilov, Y., Matthews, S. S., Langlois, M. I., Shental-Bechor, D., Greenblatt, H. M., Pandey, B. K., Smith, M. S., Paxman, R., Torgerson, C. D., Merrell, J. P., Ritz, C. C., Prigozhin, M. B., Levy, Y., & Price, J. L. (2014). Criteria for Selecting PEGylation Sites on Proteins for Higher Thermodynamic and Proteolytic Stability. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 136(50), 17547–17560. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja50951836 [↩]